The Forgotten Refugees of the Middle East

The documentary film project and a humanitarian mission in Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon

In February 2023, I travelled as part of an international crew across Türkiye, Jordan and Lebanon to film a unique documentary, “The Forgotten Refugees of the Middle East”, sponsored by The LOTE Agency and co-organised by the HOST International Ltd (Australia) and the Iraqi Christian Relief Council (USA).

The ultimate goal of the project was to capture stories of the refugees who have been stuck in limbo during the resettlement process and our crew visited the homes of refugee families and investigated the adverse effects of long-term displacement without adequate shelter, educational opportunities, health care, and hope for the future, all of which lead to the loss of human dignity.

What did we do?

Travelled across three countries: Türkiye, Jordan, and Lebanon.

Visited homes of refugee families.

Documented people’s stories of displacement, despair, and (loss of) hope.

Investigated the adverse effects of long-term displacement.

Provided humanitarian aid.

Had meetings with embassies, churches, foundations and other stakeholders.

The WHY

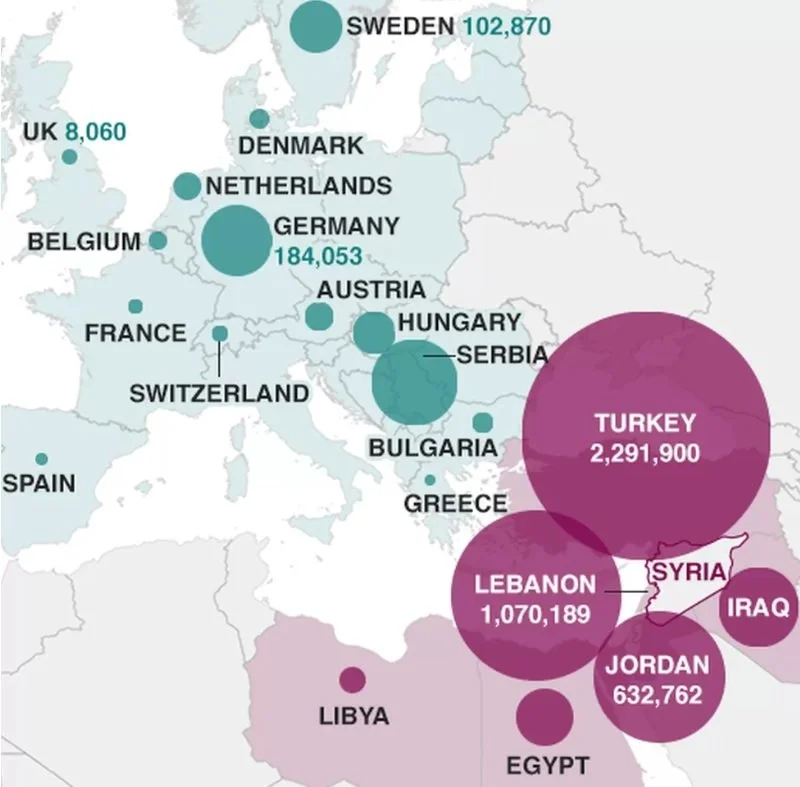

While the refugee crisis used to be widely under the spotlight a few years ago, the media attention has shifted to other conflicts and crises, leaving millions of displaced families and individuals ‘forgotten’. Yet, even if a problem is no longer a front-page headline, it doesn’t mean it has improved or been resolved. To date, the displacement has reached exhausting and unprecedented levels. As reported by UNHCR, in the world, 103 million people are living in limbo due to forced migration. There are more people claiming refuge in Jordan, Lebanon and Türkiye than anywhere else, including Europe. In Türkiye alone, 400,000 Iraqis and Syrians need resettlement from the region.

Forced migration and poor living conditions are just the tip of the iceberg - the fact that people lose human dignity over decades without adequate shelter, civil rights, education, health care and hope is no less alarming.

The documentary film, which will be released and screened in late 2023, is aimed to give voice to people’s stories, raise public awareness and draw governmental attention to the Middle East refugee crisis.

Syrian refugees registered in neighbouring countries. Source: UNHCR asylum applications by Syrian nationals from April 2011 - November 2015

The highlights

Jordan: Meetings with Embassies

In Amman, we had opportunities to meet with the USA, Australian, and Iraqi embassies officials and discuss such crucial issues as:

Humanitarian support for refugees

Humanitarian visas, intake quotas, pathways, requirements and processes.

Advocacy - opportunities for the foundations to share people’s stories.

Government policies around refugee intake.

The documentary film: distribution, publication, screening.

Connecting with relevant decision-makers and stakeholders for further dialogues.

Türkiye: Earthquakes in Adana & Hatay

While we stayed in Türkiye, the country's south was hit by the devastating earthquakes, and our team rushed to Adana and Hatay, the cities that suffered the most, to distribute aid to the victims. There's a significant refugee population living in that area, and it would be an understatement to say that seeing people who had already lost their homes and families through war and persecution re-living it again through a natural disaster.

Refugee stories

To collect the interviews, we collaborated with the Assyrian Church, community leaders and charities in the three countries that connected us with families and individuals in the most desperate state. The filming and interviewing was a mentally and physically challenging process, to say the least. When you hear first-person stories of all the horrors of war, persecution and continuous dislocation from people, it can’t but boggle your mind and evoke wholehearted solidarity with people who have suffered. Yet, not everything is so simple, and the refugee crisis is an intersectional problem rooted in political reasons, humanitarian structures, as well as in people’s cultures and mentalities. Some excerpts from the interviews will help illustrate the observations.

X. (Iraqi, Female, 30 years old)

X has lived in Türkiye with her father for 5 years. M works at a sewing factory, where Turkish co-workers constantly bully her for being a refugee. M. has only completed year 12 of school in Iraq and hasn’t had a chance to choose a profession. She can’t picture her future or career. X has been rejected for a humanitarian visa to Australia multiple times.

Her disabled father is no longer able take care of himself, and M. is taking him to doctors, but he rejects treatments because shortly after arriving in Türkiye, he developed depression.

“He’s tired of life and wants to speed up time to die”.

Yet, despite all the hurdles and adversities:

X did not complain once and smiled throughout the interview. She hopes and believes it’s all temporary.

She works hard to provide for and help her father. When asked about her hopes, she responded:

“Hope you’re all healthy and well”.

X. (Iraqi, female, 25-30 years old)

X studied in Erbil, Iraq, at a theology school, and since she arrived in Beirut, Lebanon, she has found employment as a teacher of science at a community school. She speaks English, which she learned online and would like to improve to have opportunities to move abroad and find a job. She firmly believes that hard work is the way to a better life and freedom:

“We need to work and not only take donations”.

X. (Iraqi, female, 40-45 years old)

In Iraq, X. lost a 6-year-old child, and her husband was killed in Baghdad in 2013.

Escaping the persecution, she fled to Erbil, North Iraq and was homeless until the community helped, and she relocated to Türkiye.

X. has health conditions and difficulty walking, is mentally and economically destroyed, and lives in deplorable conditions. At ‘home’, X. doesn’t even have a stove and uses a recycling oven as a heater, for which she picks up broken chairs and wood outside to burn.

And despite all the difficulties, she keeps showing up at work as a cleaner because she has two daughters and one son, for whom she feels responsible.

J., (Iraqi, female, 60-65 years old)

J. rents a pitiable living space on the basement floor. A while ago, J. broke her leg and is now considered disabled. J. lives on donations from charities and the church. She also has a sister in the USA and wants to move there to live with her. However, the questions arose when we observed that:

J. is being offered a place at an aged care facility, but she rejects help as she doesn't “want to lose privacy and freedom” and would only accept material, financial support.

Family of 6: parents, two sons and two daughters

The family have lived in Türkiye since 2015.

Over the years, they have lost four people in the family:

1977 daughter was in the army and was kidnapped.

1980’s son was shot by mistake.

1995 daughter died from a blood disease.

2009 daughter developed depression, stopped eating and passed away.

Almost everyone in the family suffers from health conditions: the younger son has a mental disorder and takes medication worth $100/month, the father lost an eye due to a bomb in Iraq, and the mother also suffers from an illness.

And yet, the family gave up and isn’t taking steps to improve their situation. Living off donations from the church and charities, even the healthier adult children are aimlessly spending time at home and not looking for work and opportunities mostly spending all day on the phone, hoping that by a lucky chance, they will be rescued someday.

Learnings & problems

The insights and knowledge we've gained during this mission, combined with our team's rich background in humanitarian work, have shed light on a number of critical issues within the humanitarian sector:

After horrific events, some people get closer to faith, while some lose it. While faith strengthens people, gives them hope and unites communities, it has also been observed that stronger faith may result in the hope of “superpowers” that will come to the rescue.

Many people give up and refuse to work, study, and learn a language to integrate into a new country.

There’s a significant knowledge gap and lack of awareness about visas, employment, and education opportunities for and among refugees.

The humanitarian system creates a culture of laziness, entitlement and dependence.

The socio-cultural factor: generations brought up in collectivist cultures and under dictatorship lack independence and critical thinking, which inherently prevents people from taking responsibility for their own lives and making decisions.

The victim mentality, which stems from trauma, circumstances as well as cultural influences, stops people from taking action.

Solutions

During this uneasy journey, our team regularly reconvened to discuss our learnings and observations, as well as the problems we identified, and speculate about possible solutions for improving and optimising the humanitarian systems:

To help people restore their dignity, a more sustainable humanitarian system has to be developed. This alternative system should be based upon encouraging people to take responsibility and action for their own lives and wellbeing, instead of (or in addition to) simply providing material aid.

Political solution: to finish the wars, persecutions and tensions, and let people return to their countries and continue their normal lives.

Most importantly, the change starts with education. It’s crucial to educate people, particularly children, on how to work, gain and apply knowledge and be independent.