Why understanding Uncertainty Avoidance is crucial in cross-cultural communications

“Should we try to control the future or just let it happen?” G. Hofstede

Before you read on, let’s start with a couple of questions.

It’s a Friday night. Do you go to your favourite restaurant and order your “go-to” dish? Or do you prefer to try something new?

Things don’t go according to plan. Do you get stressed out about it? Or do you go with the flow and see how things pan out?

In a way, the answers may depend on your personality, habits and lifestyle, but in fact, your culture plays a big role as well. To be precise, one characteristic of your culture in particular: Uncertainty Avoidance.

What does Uncertainty Avoidance mean?

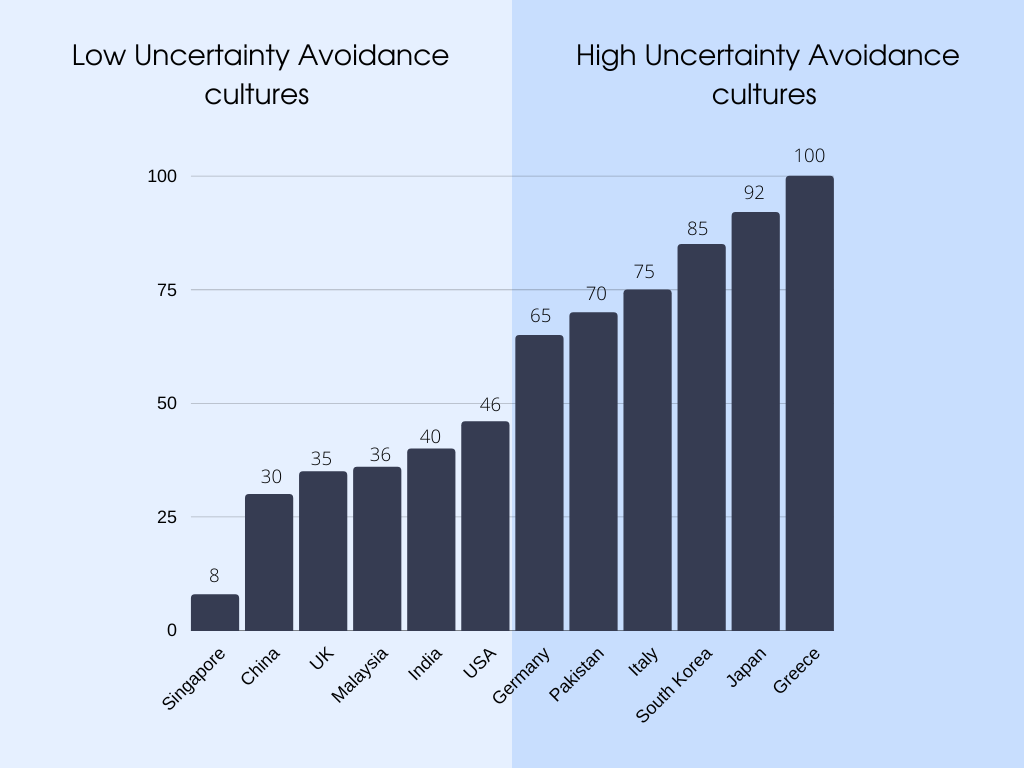

Uncertainty avoidance (UA) is one of five parameters that allow the analysis and comparison of cultures. The researcher Geert Hofstede (Hofstede 2001) introduced it within his model of cultural dimensions.

UA reflects the extent to which a particular society accepts, or feels threatened by, the unknown, new and ambiguous.

In the cultures that score high on UA, individuals try to minimise risks and chances of unpredictable events. Unstructured situations cause anxiety and people use careful planning, rules and regulations to keep everything under control.

At the other extreme are societies with a low UA index, which are more risk-taking. They welcome new experiences and adapt more easily to unfamiliar environments faster than their low-UA counterparts. These cultures also have quite relaxed attitudes towards rules and regulations.

Cultural Behaviours

To better understand this dimension, let’s look at its social implications.

Innovation and change

Low-UA cultures value creativity and innovation, and adopt trends and new technologies much faster. On the opposite, high-UA cultures remain more conservative and reluctant to try something unfamiliar. Instead they stick to the proven, trusted options. This can create a challenge for marketers aiming to bring a new product or technology to international markets.

Finances

UA index manifests itself in the attitudes to saving money. High-UA cultures approach their financial operations, such as budgeting and saving, with a greater care. After all, having enough savings means better security of one’s future. To work effectively with multicultural customers, banks must have a thorough understanding of their values and needs, to ensure their services and communications are suitable and relevant.

Employment

In the modern world, a stable job is the classic symbol of confidence in the future. In high-UA countries, many people would choose civil service, which guarantees job security, over a job in a private sector, even if it’s better paid. A great example is Japan, where a position in a government ministry is considered more prestigious than building a corporate career (Yoshimura and Anderson 1997).

Workplace and leadership

Cultural clashes are not uncommon at multicultural workplaces. If the management and employees belong to cultures with a different UA index, they will have conflicting expectations regarding rules and fundamental work processes. For instance, if the director is from a high-UA culture, the low-UA employee will perceive his management style as oppressive and rule-oriented. The director, in turn, won’t be satisfied with the “unreliable” and “irresponsible” employee.

Why is this so important to understand?

What we’ve discussed here is the tip of the iceberg. Understanding cultural differences is important in an infinite number of social situations. From business and marketing, to education, management, policy making, and many more. Once you understand a culture’s attitude to Uncertainty Avoidance, you can communicate more effectively and establish a deeper connection. Whatever your cross-cultural communications objectives, understanding your audience’s Uncertainty Avoidance is crucial to a successful outcome.

References:

Hofstede, G. (2001) [1984]. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviours, Institutions and Organizations across nations. London: Sage.

Yoshimura, N., & Anderson, P. (1997). Inside the Kaisha: Demystifying Japanese business behavior. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press. 193.